Market volatility: Super’s silver lining

If your super balance has suffered from recent market volatility there may be opportunities available now that weren’t before. Here are a few worth exploring.

Entitlement to an Age Pension

If you’re 67 or older, a lower super balance may mean you now qualify for the Age Pension or a higher payment if you are already getting an Age Pension.

Most assets, including super and super pensions, are assessed under the Centrelink asset test to determine eligibility.

The Age Pension is subject to both income and asset tests, and the one resulting in the lower payment applies.

If your assets fall below the cut-off threshold, you may qualify for a part Age Pension (subject to the income test). If they’re below the full pension asset test threshold, you may receive the maximum entitlement.

The table below shows the asset thresholds for receiving a full pension, as well as the cut-off point beyond which you’re no longer eligible:

If your assets were between the thresholds and have reduced, you may be entitled to a larger Age Pension than before. As an example, if you are a single Age Pensioner and not getting the maximum Age Pension because your assets are too high, then a reduction in the value of your assets by $10,000 will increase your Age Pension by $780 per annum or $30 per fortnight under the asset test. This represents a 7.8% increase in entitlements which may be more than the income actually produced on assets.

Ability to make further non-concessional contributions

That dip in your super balance may allow you to contribute more into super from 1 July 2025. How much you have in super and super pensions at 30 June of the previous financial year can impact how much you can contribute as a voluntary ‘after-tax’ non-concessional contribution (NCC) in the current financial year.

For instance, if your total super balance (TSB) – which includes all your superannuation interests as at 30 June 2025 (including both super and pension accounts) – is lower, you may be able to make a larger NCCs from 1 July 2025.

As a reminder, the ‘bring-forward rules’ allow eligible individuals to contribute up to three years’ worth of NCCs in a single financial year. This can be especially useful if you have a lump sum to invest, such as from an inheritance or the sale of an asset or property.

However, the amount you’re able to contribute under these rules will depend on your TSB as at 30 June 2025. With the TSB thresholds set to increase from 1 July 2025, new contribution opportunities may become available in the new financial year.

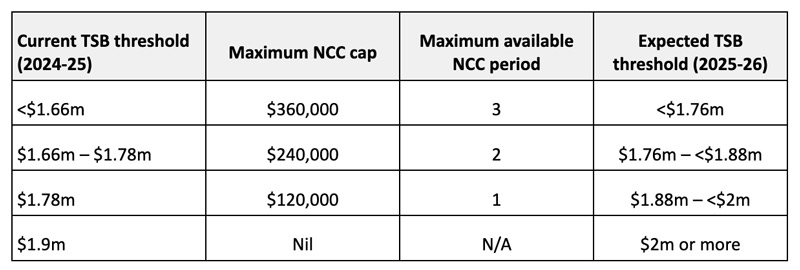

The table below outlines the TSB thresholds that will apply when determining your bring-forward cap for 2025/26:

Commence an account based pension

Starting your first account-based pension (ABP) during a market dip can be a smart move, especially if you’re within the general transfer balance cap. The cap is currently set at $1.9 million for anyone starting their pension for the first-time this year, and it limits how much you can transfer into a pension account.

As a background, when you transfer funds into an ABP, that amount counts towards your transfer balance cap. However, any growth on your investments after that point doesn’t affect your cap. So, if markets recover while your money is in the pension phase, the gains stay within your account and you won’t be penalised for going over the cap.

And more good news – if you haven’t yet started a retirement phase income stream like an ABP, the general transfer balance cap is set to increase to $2 million from 1 July 2025, allowing you to invest a further $100,000 in the tax-free pension phase!

Seizing the moment

A drop in your super balance might present new opportunities, talk to us to see how recent market volatility could help shape your retirement strategy.

Downsizer Super Contributions: Dispelling three myths

Billions of dollars in downsizer super contributions have been made since its introduction in 2018. Downsizer contributions are popular, but three common misconceptions keep them from being more so.

Downsizer super rules allow people aged 55 and over who sell their home to contribute up to $300,000 into super. The rules say that you can be too young to make the contribution, but you can never be too old. This is why people who usually can’t make contributions due to their age love downsizer contributions.

People with large amounts to contribute also love downsizer contributions because they allow you to contribute over and above the ordinary contribution cap limits.

The “downsizer super contributions” has caused confusion about who is eligible and when. It is important to speak to an adviser to confirm your eligibility, but don’t be fooled by the following three myths which stop people from making a downsizer contribution.

You must“downsize” your home

A common misconception is that you must “downsize” by purchasing a cheaper home. While selling your home is required, there is no obligation to buy a less expensive property – or even to purchase a new home at all. In fact, some people choose to “upsize” and make a downsizer contribution using other savings. This is completely acceptable (see below).

Proceeds must come directly from the sale

The downsizer contribution does not need to come directly from the sale proceeds. If all the sale proceeds are used to purchase a new home, the individual can use savings elsewhere to fund the contribution. Individuals may also make a downsizer contribution in the form of an ”in-specie” contribution of another asset like listed shares so long as the value of the asset is within the allowable limits i.e. the lesser of sale proceeds or $300,000. Remember only self-managed-super funds generally accept in-specie contributions and these are limited to specific assets like listed shares, business real property and units in a widely held unit trust such as a managed fund.

You must live in the home at the time of selling

Another misunderstanding is that you must be living in the home when it’s sold. This is untrue but it is necessary to have lived in the home at some point. This requirement exists because eligibility for a downsizer contribution depends on qualifying for at least a partial main residence capital gains tax (CGT) exemption. While you must have previously lived in the home, it does not need to be your main residence when you sell it.

Conclusion and helpful checklist

Understanding the downsizer rules will help you to ignore the myths. It is important you speak to a qualified adviser to confirm your eligibility, but the following checklist may help you check off on your eligibility..

- You are age 55 or over at the time of making the contribution

- You have sold an eligible home (dwelling)

- You or your spouse have sold an interest in a dwelling held for at least 10 years by either yourself, your spouse or former spouse

- The disposal is at least partially disregarded under the main residence exemption or would have been eligible for the exemption had the property not been a pre-CGT asset

- You will make the contribution within 90 days of receiving the sale proceeds

- The contribution is within the lesser of $300,000 and the sale proceeds

- You have not made a downsizer contribution from the sale of another home

Essential reminder

Don’t forget to submit the “Downsizer contribution into super form” (NAT 75073) to your fund with or before the contribution is made.

Seven changes impacting your super in 2025

Superannuation rules are always changing, and 2025 is set to bring some updates that could affect your retirement savings. Whether you’re just starting to build your super or already planning for retirement, keeping up with these changes can help you make informed decisions. Here’s what’s on the horizon.

1. Possible tax changes for large superannuation balances

The government is looking at increasing taxes on large super balances. The proposal would add an extra 15% tax on the earnings of super balances over $3 million, starting from 1 July 2025. This has been a hot topic, with debates about whether the tax system for super is fair.

The proposal made it through the House of Representatives in 2023 but ran into problems in the Senate in late 2024. To pass, the government needs support from minor parties and independent senators, but many are pushing back against key parts of the plan, such as taxing unrealised gains (profits on investments that haven’t been sold) and not adjusting the $3 million threshold over time.

With a federal election coming up, it’s unclear if this tax change will go ahead. If it doesn’t pass soon, it may be delayed or scrapped altogether. The Senate will revisit the issue in February 2025, so we’ll have to wait and see what happens next.

2. Increase in employer superannuation guarantee contributions

A key change in 2025 is the rise in the super guarantee (SG), which is the portion of your wage that your employer must contribute to your super fund. From 1 July 2025, the SG rate will increase from 11.5% to 12%. While this might seem like a small increase, it can make a significant difference over time, helping your retirement savings grow. If you’re an employee, this means more money going into your super, but it’s also worth checking if it affects your overall salary package.

3. Potential increase to transfer balance cap

Although contribution caps increased in July 2024 due to inflation adjustments, they are not expected to rise again in July 2025.

However, the transfer balance cap (TBC) – which limits how much super can be moved into a retirement pension – will increase from $1.9 million to $2 million on 1 July 2025.

This change mainly affects people who haven’t yet started drawing a retirement income from their super. If you already receive a pension from your super, you might still benefit from a partial increase, depending on your individual circumstances.

4. Impact on total superannuation balance

As the TBC rises on 1 July 2025, the total super balance (TSB) limit will increase as well. This limit affects how much you can contribute to your super using after-tax dollars, known as non-concessional contributions (NCCs).

The expected increase in TSB thresholds will determine how much extra you can contribute, including whether you can use the bring-forward rule, which allows you to make larger contributions over a shorter period. The table below shows a breakdown of the expected limits for 2025.

As can be seen, if your TSB is below $1.76 million, you can contribute up to $360,000 over three years. However, as your TSB increases beyond this amount, the limit on how much you can contribute gradually reduces. Once your TSB reaches $2 million or more, you will no longer be able to make additional NCCs.

These changes may create opportunities for some individuals to grow their super, but it’s important to understand how the new limits apply to your personal situation.

5. New rules for older legacy pensions

In December 2024, the government introduced new rules to give people more flexibility in managing older “legacy pensions.”

For years, some retirees with lifetime, life expectancy, and market-linked pensions in self-managed super funds (SMSFs) have faced strict rules that made it difficult to change or adjust these pensions. These products can no longer be started in SMSFs, and many people have been stuck in outdated pensions that no longer suit their needs.

Previously, the only way to change these pensions was to convert them into similar products, which came with limits on how reserves could be allocated that did not count towards the member’s contribution caps.

But with the new rules now in place, people with legacy pensions have five years to review their options and make changes if needed. Since these decisions can be complex, it’s a good idea to speak with a financial adviser, especially one who specialises in SMSFs, before making any changes.

6. Improved super fund performance and transparency

Large APRA-regulated super funds are under pressure to deliver better performance and be more transparent with their members. In 2025, expect to see:

- Continued focus on underperforming funds: funds that don’t deliver strong returns may face more scrutiny or even be forced to merge.

- Better reporting on fees and investment performance: members should receive clearer information about where their money is invested and what fees they’re paying.

- Comparing super funds has become easier, helping you make more informed decisions about where to keep your retirement savings.

Comparing super funds has become easier, helping you make more informed decisions about where to keep your retirement savings.

7. Technology and digital innovation and super

Technology is playing a bigger role in superannuation, and 2025 will likely see more innovation. Super funds are investing in better online tools, mobile apps, and artificial intelligence to help members track their savings and make smarter investment choices. If you haven’t already, it’s worth exploring your super fund’s digital tools to take control of your retirement planning.

Final thoughts

Superannuation is a long-term investment, and small changes can have a big impact over time. With the start of a new year, take the time to review your super, stay informed about potential changes, and consider speaking to a financial adviser if needed. With the right strategies, you can make sure your super is working hard for your future retirement.

Christmas and tax

With the festive season just around the corner (or already under way), many business owners will be gearing up for year-end celebrations with both employees and clients.

Knowing the rules around FBT, GST credits and what is or isn’t tax deductible can help avoid unwelcome surprises on the tax front.

Holiday celebrations generally take the form of Christmas parties and/or gift giving.

Parties

Where a party is held on business premises during a working day, is attended by current employees only and comes in at less than $300 a head (GST-inclusive), FBT does not apply, the cost of the function is not tax deductible and GST credits cannot be claimed.

Where the function is held off business premises, say at a restaurant, or is also attended by the employees’ partners, FBT applies where the GST-inclusive cost per head is $300 or more, but not where the cost is below the $300 threshold, as it would be regarded as a minor or infrequent benefit. Where FBT applies, it applies to the entire cost of the event, not just to the excess over $300, while the cost of holding the function is tax deductible and GST credits can be claimed.

Where clients also attend, FBT will not apply to the cost applicable to them (not being employees), but those costs will not be tax deductible and GST credits will not be available.

Gifts

First, you need to work out whether the gift itself is in the nature of entertainment – for example, movie or theatre tickets, admission to sporting events, holiday travel or accommodation vouchers.

Where the recipient of an entertainment gift is an employee, and the GST-inclusive cost is below $300, the minor or infrequent exemption may apply so that FBT is not payable, in which case the cost will not be tax deductible and GST credits are not claimable. For larger entertainment gifts to employees, however, FBT applies, the cost is deductible and GST credits can be claimed.

Where the gift is not in the nature of entertainment and it falls below $300, the FBT minor or infrequent exemption may apply – for example, Christmas hampers, bottles of alcohol, pen sets, gift vouchers. But because the entertainment rules do not apply, the cost of the gift is tax deductible and GST credits are claimable.

Where a gift is made to a client, the $300 FBT minor benefit exemption falls by the wayside, as long as it is not an entertainment gift and the gift was made in the reasonable expectation of creating goodwill and boosting future sales. Such gifts are uncapped (within reason) and are tax deductible to the business. GST credits are also claimable.

Best approach for employees

Provided it’s not a regular thing, taking employees out for Christmas lunch or dinner escapes FBT, as long as the cost per head stays below the $300 threshold. While the cost of the function will still be non-deductible, that has much less of a cash-flow impact on the business than the grossed-up FBT amounts.

Combined with a non-extravagant off-site Christmas party, making a non-entertainment gift costing up to $299 is a very tax-effective way of showing your appreciation. Gift cards are always well-received and even where they can be used to make a wide variety of purchases (including theatre tickets and the like), they will not be regarded as an entertainment gift, which means the cost is tax deductible and GST credits can be claimed.

Best approach for clients

While FBT is off the table for business clients, making a non-entertainment gift (tax deductible; no dollar limit) is actually much more tax-effective than wining and dining a key client (non-deductible entertainment). If you put some thought into what gift to buy a client and in some cases deliver it yourself, you may make much more of an impact than joining them in one of many restaurant meals in their already crowded Christmas calendar.

If you need help on the tax treatment of holiday celebrations and gifting, please give us a call.

Unwrap your future: 12 super tips for a merry and bright retirement

Christmas is a time for giving, but it’s also a great time to give your future self the gift of financial security. Here are 12 simple superannuation tips to help you make the most of your super fund – wrapped up with a touch of festive cheer!

1. Consolidate your superannuation

If you’ve worked multiple jobs, you might have multiple super accounts. Consolidating them into one fund can save you money on fees, similar to decorating one Christmas tree instead of several. The good news is that consolidating is easy through ATO online services or your myGov account where you can also search for lost or unclaimed super. Before consolidating, consider potential impacts like the loss of insurance coverage, fees, investment options, and tax implications to ensure the transfer aligns with your needs and adds value.

2. Review your investment strategy

Your super is an investment for your future, so make sure it aligns with your goals and risk tolerance. Think of it like choosing the perfect star for your Christmas tree – get it right, and it will shine brightly for years. For self-managed super funds (SMSFs), it’s a legal requirement to have a documented investment strategy aligned with your objectives, which must be reviewed regularly. Now is a great time to ensure your strategy supports your retirement goals.

3. Check your insurance coverage

Many super funds offer default insurance, including life, total and permanent disablement (TPD), and income protection coverage. It’s essential to review your cover to ensure it provides adequate protection for you and your family. If you manage an SMSF, you’re also required to consider and document the insurance needs of each member as part of the investment strategy. Seek professional advice to ensure your current cover is sufficient for death, disability or illness.

4. Check your fund’s performance

Not all super funds are created equal, and performance can vary significantly. Regularly check your fund’s performance compared to others to ensure it’s performing. If your fund’s performance is underwhelming, consider revisiting your investment strategy or switching to another fund that better aligns with your retirement goals.

5. Nominate your beneficiaries

Super isn’t automatically part of your estate, so it’s important to nominate valid beneficiaries to ensure your funds go to the right people. Without a valid nomination, your super fund may decide who receives the benefits, regardless of your Will. Regularly review your beneficiary nominations, especially when circumstances change, to ensure they are up to date and reflect your preference.

6. Make extra contributions

Even small additional contributions can make a big difference to your super balance at retirement thanks to compounding returns. It’s like adding an extra treat to a Christmas stocking – small now, but a delightful surprise in the future. In addition to the 11.5% employer super guarantee contributions for 2024/25, adding extra contributions through salary sacrificing or personal after-tax payments can boost your retirement savings. Just be mindful of contribution caps to avoid extra tax. Small sacrifices now can lead to substantial benefits later.

7. Salary sacrifice

Salary sacrificing is an efficient way to boost your retirement savings and reduce your tax. By redirecting part of your pre-tax salary into your super fund, you can benefit from lower tax rates, allowing more money to work for you in the long term. It’s an easy way to start saving for the future without feeling the pinch today, and over time, compounding returns will help your super grow.

8. Claim your government co-contribution

If you earn below a $60,400 a year and make a voluntary contribution to your super, the government may top up your super with a part co-contribution. The maximum co-contribution is $500. To receive this maximum amount your income must be below $45,400 and you must contribute at least $1,000 as a personal after-tax contribution into super. This is a great way to boost your super savings and is a government bonus, much like finding an unexpected gift under the tree. To be eligible there are several other rules, so check if you qualify and take advantage of this opportunity to grow your retirement savings.

9. Explore spouse contributions

If your spouse earns less than $40,000 pa, you can contribute to their super fund and potentially claim a tax offset of up to $540. This is a great way to help boost their retirement savings and potentially reduce your taxable income in the process.

10. Plan for transition to retirement

If you’re nearing retirement, a transition-to-retirement (TTR) strategy could help you make the most of your savings and ease into retirement more comfortably. This strategy allows you to draw down some of your super while still working part-time, supplementing your income without fully retiring. It’s a way to boost your savings and ensure a smooth transition to retirement, making your golden years as stress-free as possible.

11. Review fees

Super funds charge various fees for managing your money, and these can add up over time, reducing your returns. It’s important to review the fees associated with your super to ensure you’re not overpaying. Much like trimming unnecessary expenses from your Christmas shopping list, minimising fees helps your super balance grow. Check if you’re getting good value for the services provided and whether switching to a more cost-effective option could be beneficial.

12. Seek professional advice

If you’re unsure about any aspect of your super, seeking advice from a financial adviser can be a great step. A financial adviser can provide tailored advice, helping you navigate decisions about your super, investments, and retirement planning. Think of them as your financial Santa’s helpers, ensuring your super journey stays on track and guiding you toward the best financial decisions for your future. It’s always worth consulting an expert to maximise the benefits of your super and financial planning.

The last word …

By ticking off these 12 tips, you’ll be giving yourself the ultimate Christmas present: a brighter and more secure future. Merry Christmas and happy super planning!

Interest deductibility and investment properties

With interest rates remaining stubbornly high, and some property investors bailing out altogether, others are taking steps to refinance their debt in order to secure a lower rate and obtain better terms.

Before deciding to go down the refinancing route there are broader financial issues to weigh up and you may need to seek separate financial advice that takes into account your personal and financial circumstances. This article only examines the tax consequences of refinancing your investment property loan and some other issues around interest deductibility.

Basic rule for interest deductibility

The basic rule is that where you borrow money to acquire an income producing asset, the interest is deductible against your assessable income generally, including income from salary and wages. It’s about following the money and being able to demonstrate that a loan was used for income producing purposes. Any security given over a loan does not determine the deductibility of the interest.

Maximising tax deductible debt

There is nothing improper or untoward about maximising your tax deductible debt. We live in an after tax world and it’s perfectly legitimate to factor tax into your financial decision making.

Lower rate on refinancing

Where the refinancing involves no more than obtaining a reduced rate or better terms, there has been no additional borrowing and the interest on the new loan remains deductible in full, assuming the property is let or available to let.

Releasing equity

Where the refinancing releases equity in the investment property, interest deductibility depends on how the additional loan funds are applied. If they are used to maintain or renovate the investment property (or to buy other income producing assets), all the interest payable on the increased loan balance will be deductible.

However, where all or part of the equity released is applied for private purposes (like renovating the house you live in, to pay for a holiday or to buy a car), the interest would need to be apportioned between the amount originally used to acquire the investment property (deductible) and the amount used for private purposes (non-deductible).

Refinancing costs

Refinancing costs for the investment property such as exit fees, valuation fees, break costs and legal fees are deductible over five years or the term of the new loan if that is shorter.

Change in use

What if there is a change in use of the investment property? You might decide to move into the property yourself or to make it available to a family member free of charge. As soon as the investment property stops being used to generate rental income, the interest associated with the loan taken out to acquire the property stops being deductible.

By the same token, if you move out of your main residence to go and live somewhere else and you put tenants in, any interest on the mortgage over the property will become deductible.

Debt in the wrong place

Sometimes, through circumstances beyond your control, you can end up having debt in the wrong place. For example, you may have a mortgage over the house you live in and inherit the house of a relative which is unencumbered by debt. If you decide to keep the inherited property and put tenants in, you will have non-deductible home mortgage interest as well as an investment property that is debt-free.

While you could borrow using the inherited property as security and use the funds to pay off your home mortgage, that would not get you a tax deduction, as the borrowed funds would have been used to pay off private debt. Remember, it’s the use to which the funds are put that determine tax deductibility – not the nature of the security provided. The only way to make the interest tax deductible in this situation would be through a change in use. For example, you may decide to move into the inherited property and let out your main residence.

Forced sale

Real estate values can go down as well as up, and sometimes life’s events (rising interest rates, unemployment, illness, divorce) can leave the property owner with no other option but to sell the property, sometimes with part of the borrowing remaining unpaid. Any interest on the outstanding balance would generally be tax deductible, although the ATO would expect the investor to make a reasonable effort to pay down the remaining debt rather than acquire more assets.

Before deciding how to refinance an investment loan or taking any other steps that could impact on the tax deductibility of interest, come in and have a chat with us. We may be able to help you protect the interest deductibility you are legitimately entitled to.